A glance at the life of Ghaffar Hosseini

Esmail Nooriala

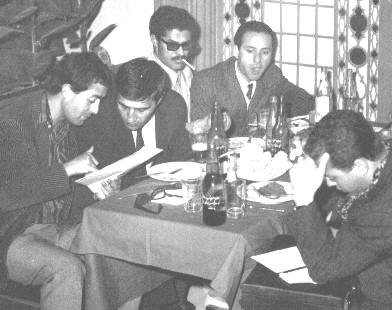

Esmail Nooriala and Ghaffar Hosseini in Shiraz -1972

Ghafar Hosseini was born on April 2, 1935 in a small village in the West of Iran called Aligudarz. He was believed to be a descendant of the prophet Mohammad. Such people are known as "Seyyed" and have a special position in the society. His father was a devoted Moslem and peasant in the village and people liked and esteemed him because of his blood lineage. He wanted his son (the elder of 3) to become a Mullah and, to this end, taught him the Koran and eulogist poems about the martyrdom of the Shiite saints. Ghaffar had a nice childish voice and participated in the passion plays of the village.

What changed his life was a happening that put its mark on his sole forever. He had a male dog that was very dear to him. In the middle of the village there was a castle in which resided the grand owner of the village (the Feudal or Arbaab) and he had a female dog. One day, his men found out that Ghaffar's dog had an intercourse with Arbaab's bitch. This made him furious and could not tolerate what he considered an insult to his dignity and power. He ordered that Ghaffar and his dog be brought to the castle and, in front of the 10 year old boy, he shot the dog.

During that night of 1945 Ghaffar decided to escape the village. It was in the middle of World War II, the country was occupied by Allied Forces and jobs were scarce for a small villager. But he had decidedly embarked on a journey that would change his course of life. He first went to the nearest town, Borujerd. The only way he could survive there was to become a domestic servant in a wealthy trader's house. While working, he began to learn writing and reading Farsi by the help of his Koranic knowledge. During his five years in that house, and despite the harsh conditions of work, he finished his first part of high school studies. He even tried to learn English and picked up a few words and sentences.

In 1951, he left Borujerd for Abaadaan. This was a major port on the top of the Persian Gulf, developed by British Petroleum Company that had its grip on the Iranian oil fields for a century. He was employed in the Refinery as a simple worker. Within 3 years he got his diploma. Those years were hectic times. Allied forces had left the country but the Soviet army was successful to enforce the Iranian Communist Party as the party of Intellectuals. A parallel movement was that of the Nationalization of Iranian Oil Industry under the leadership of the Prime Minister Dr. Mohammad Mossadegh. Abaadaan was the hotbed of the nationalist activities. But Ghaffar, coming from a hard and poor background, was mostly absorbed towards the Communist Party that advocated social justice and claimed to be representing the working class. Ghaffar participated party's classes and demonstrations. Many times he was arrested and beaten by the security forces.

In 1953 there was a CIA-inspired coup d'etat in Iran and Dr. Mossadegh was overthrown. Then there began a witch hound to purge the Communist elements. Many members of the party were executed by the firing squad. Ghaffar was known in Abaadann to be a communist and could not stay in the city. He left his job and, six months after the coup d'tat, he arrived in the capital, Tehran, with empty pockets. The atmosphere was tense and people with no place to live and no job to attend were natural suspicious elements. Ghaffar decided to enroll in the army and become a soldier before being caught.

Two years later, in 1955, Ghaffar was back in the streets. He took some errand jobs and, for the first time, contacted his family in the village. He also began to learn English language and studied Persian literature. He wrote his first poems in 1957 and soon was able to establish relationship with literary figures and magazines.

A year later, he was employed by the new National Iranian Oil Company to work in pumping stations that were being built along the pipe line that moved oil from the south to the north of the country. Now he had enough money to set up a descent life and attend to what he was good at, writing. In the summer of 1961 he met his future wife, Farangis, in the company's club. As a high school student, she had come to the region to spend her summer holidays with her uncle's family. They soon fell in love but Farangis had to leave at the end of the summer and Ghaffar lost her. He was too timid and shy to ask the uncle about her.

That summer, Ghaffar had done one more thing. He had participated in Tehran University's entrance exams and was successful in enrolling in the English Department of the Literature Faculty. Being far from Tehran, he of course could not attend classes but in those days attendance did not play a major role in students' grades.

In 1961, I was a student of English in the same department but did not meet Ghaffar until the end of the academic year, i.e., summer of 1962. I was 8 years younger than him and when he, amongst his class-mates, chose to come towards me, introduce himself and tell me about his situation (being unable to attend classes) and ask for my help, I welcomed hid friendship. He was a mature and likable guru for me. During his two month of stay in Tehran, we became close friends. I was involved in literature too and had connections with many literary figures. Ghaffar was welcomed in our literary modernist circle.

During that summer, Ghaffar was lucky enough to meet Farangis's sister by sheer accident in Tehran University and, through her, met with his love. They soon decided to marry. It was a simple ceremony in her house we me and a few other friends present. A few days later, the couple left Tehran for Ghaffar's work place.

In 1963, I and Ghaffar finished our University studies and he was able to transfer his job to the Oil Company's central office in Tehran. The family had now a son, named Manelli. This is the name of a character created by the father of Iranian modernist poetry, Nima Yushij. The adaptation of the name showed Ghaffar's focus on Persian modern poetry. At the same time, through his acquaintance with Bahman Forsi, the renowned Iranian playwright, he became interested in theatre and began to translate short plays and write theatre reviews.

In 1964 Ghaffar and I were amongst those young poets and writers who established a modernist literary publication house called "Torfe" (meaning "Fresh"). We published several books and a literary periodical.

From Left to right: Ahmad Reza Ahmadi, Mohammad Ali Sepanlou, Ghaffar Hosseini, ????, Esmail Nooriala - 1965

In 1965 I was invited to become the literary editor of Negin Monthly and Gahffar joined me as a theatre critic. In the same year, we decided to continue our university studies and enrolled in the Faculty of Social Sciences. Two years later we got our M.S. degrees.

In 1967, Ghaffar decided to go to France. He had begun to learn French for a vfew years. His trip was to take place under the pretext of continuing his studies but he had made his mind up to go to North Vietnam and fight for that country. He had still a lot of love and dedication for his Communist upbringing.

As he told me later, he was not admitted to that army and, instead, he enrolled in Sorbonne for his doctorate degree. His wife and children were left in Iran, waiting for his return. Two years later he came back, totally disillusioned with the French Communist Party and the Stalinist camp. For the first time, I could detect his inclination towards becoming an "intellectual" rather than a "freedom fighter".

We both were invited to teach in Tehran University and, thus, Ghaffar felt that he had reached the zenith of his life. Many times before, he had told me that his ultimate goal was to become a full-fledged university lecturer. We both worked at the Plan and Budget Organization too.

Nevertheless, two years later he felt that he could not tolerate the political atmosphere of Iran that was totally tilted towards the dictatorship of the king and formation of guerilla organization. He gave me the manuscript of his poems and asked me to publish his book in his absence which I did and this is the only published book left of his penned works.

Cover of Ghaffar's Collection of Poems

In 1973, I decided to go to the University of London and begin my studies for a doctorate degree in Political Science. Ghaffar soon decide to move to London and for five years we were again together. He had a small room in Paris and commuted between the two cities, trying to finish his dissertation for Sorbonne.

He also sold his house in Tehran and bought a bed-and-breakfast in London and became a self-employed freeman. His second son, Mazdak, was born in London. Mazdak was a revolutionary figure in pre-Islamic Iran who fought for the communal ownership of properties. He was brutally put to death. Thus, communist ideas, in socialist disguise, were still lurking in Ghaffar's mind.

Soon came along the Iranian Revolution of 1978 but in a religious wrapping. Ghaffar was furious. All his life he had hated the Mullahs and now his long-awaited revolution had realized under the leadership of an Ayatollah. Nevertheless, he decided to go to Iran and participate in the political developments. He sold his bed-and-breakfast, bought a small apartment for his family, and went back to Iran, resuming his classes in Tehran University. I met him in his new house in Tehran a few months after the revolution. He was poised to stay but I was not supposed to be there for long and went back to London a few months later.

Ghaffar could not last for more than a year. The Islamic regime, under the banner of Cultural Revolution, began to purge the "corrupt and Westoxicated elements" and closed the sociology departments in Iran's universities.

Ghaffar too lost his job to the purge and had to leave the country. He again sold his house and arrived in Paris to join Farangis and Mazdak and to begin the rest of his life with a hollow chamber in his chest. He thought that he will never see his country again.

He finished his doctorate at Sorbonne at a time when he saw it as an absolutely irrelevant achievement. He participated in the formation of the Union of Iranian Writers in Exile and became an active member of the opposition. Nevertheless, soon he began his fights with Farangis that finally led to their separation and divorce. He left their apartment to his ex-wife and his second son and bought a small newspaper shop in the fringes of Paris, working and living in the same place. I heard, through our mutual friends, about his bouts of depression. He did not have any contact with me during those days.

In 1989, Manelli called me and said that his father was in London and in his way back to Iran and wanted to see me before his departure. I went to see him. Within five years, he had turned into an old broken man. He told me that he had lost all his hopes for the betterment of the political situation in Iran and had contacted the Iranian embassy in Paris to be allowed to go back safely. There, they had asked for a written guarantee that he would not get involved in political activities once back in Iran. We hugged each other for the last time and he set sail for his beloved country.

From then on, my contact with him was through Manelli who used to come to my house every week. We talked about Iranian culture and literature during these meetings and he told me that his father was doing fine in Iran.

In 1994 I immigrated to USA and my contact with Ghaffar and his family members diminished. But, through the Persian media coming out of Iran, I came to know that he had become one of the dissident members of the outlawed Union of Iranian Writers and was participating in discussion about the freedom of press and fighting the censorship in Iran. I wondered what the reaction of the security forces will be. They had become very intolerant towards the dissidents and had began a process that later became known as the "Serial Murders". I felt that he was in dire danger but there was nothing I could do for him.

In the winter of 1996, a friend called me from Paris to inform me about Ghaffar's death. They had found his body in his apartment with the entrance door to the apartment left ajar. He had been dead for two days.

I contacted Farangis in Paris. She confirmed the news and said that she was going to Tehran to see what had happened to her ex-lover and father of her children. She also told me that Ghaffar's body was going to be given to his brother who was still residing in the old village. A few days later, they took Ghaffar back to his birth place, Aligudarz. The circle was, thus, completed.

Two years later some lights were shed on Ghaffar's death by an Iranian journalist - arrested and tortured by the security forces, i.e. Faraj Sarkuhi. Iin his book, he tells the story of his torturers coming to him. He was told by them that they had killed a score of writers including Ghaffar due to their activities in Iranian Writers' Association.

A part of Sarhuki's book on the murder of Iranian writers

Ghaffar had been killed by a gang of security agents related to Ministry of Information under the leadership of someone named Saeed Emaami.

Februray 2006 - Denver

Return to Nooriala's Home Page